$500 gone — only spotted because of a notification from a credit card company. $1,500 gone — bringing a bank account perilously close to empty. $3,000 — a college education fund depleted to mitigate the damages. These stories, scattered throughout forums across the internet, read like some niche B plotline for the newest season of Law & Order: Cyber Crimes Unit. In reality, they’re all stories of parents caught off guard by their kids’ online gaming charges. And in many cases, this spending comes in the form of a term often uttered in hushed tones by concerned parents: loot boxes.

As a concept, loot boxes are not new. The toy industry has always relied on our desire to get our hands on what the world has declared rare and important — and our willingness to sink money into that pursuit. But it wasn’t until a game company took the idea of loot boxes too far that the world — and its governments — began to take notice.

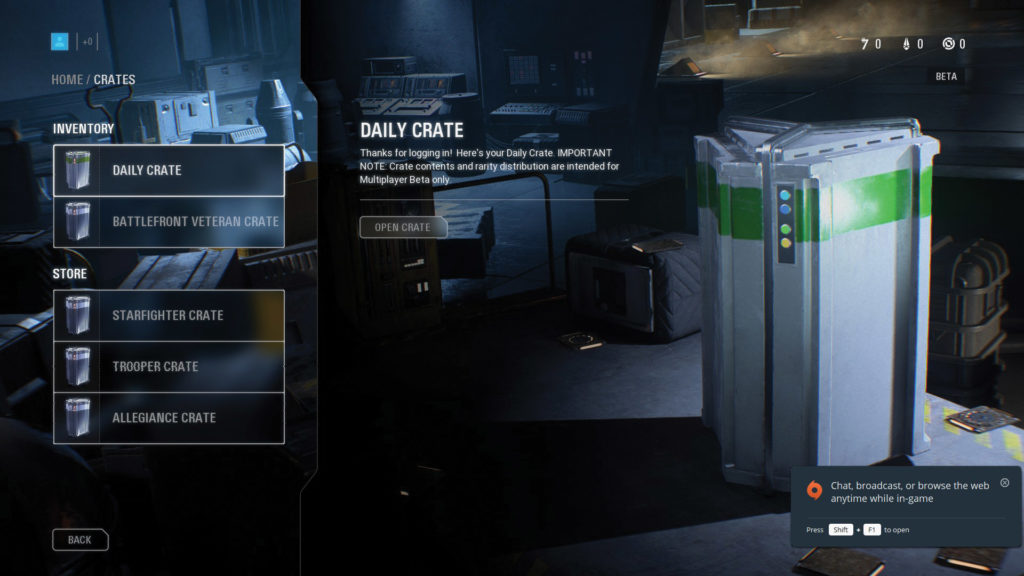

In 2017, gaming giant Electronic Arts (EA) released Star Wars Battlefront 2, a sequel to its remake of the popular Star Wars online first-person-shooter game. Immediately, players noticed something concerning: Major competitive components of the game were locked away from the start and could only be unlocked by massive amounts of gameplay — or by paying for randomized loot boxes and hoping that you got the items you needed. This pay-to-win dynamic made fans furious, and they made enough noise that the industry began to take notice.

“Probably every single person you’ve spoken to has mentioned when the Battlefront 2 loot boxes came out,” Dr. Brett Abarbanel, director of research at the University of Nevada Las Vegas’s International Gaming Institute, correctly guesses in an interview. Abarbanel has studied links between gambling and video games for the past 10 years. An avid gamer and poker player, she wanted to make clear the line between randomness and gambling — and how EA crossed it.

“Elements of randomness have shown up for almost as long as video games have been around,” she points out, citing examples such as critical hits and other game mechanics that have variable, non-100% chances. It becomes gambling, however, when you introduce a cost and an incentive to pay it repeatedly. “A good, brief definition would be that you’re risking something of value on an outcome that’s uncertain,” Abarbanel says, “but this includes a vast variety of things — … any sort of minimal item where you would risk something.”

When asked to compare more traditional forms of gambling to their video gaming counterparts, she laughs. “This is like an hour-long lecture,” she says. But in the end, her answer was admirably concise — and immediately recognizable.

“The first parallel we see in loot boxes is slot machines. There’s the [random number generator (RNG)] function that’s built in to a computer algorithm, there’s the colorful aesthetic, too. … There might be music associated with it, or different sounds, and then there might be the surprise element. There’s a drama that might be parallel to the drama of a slot reel [in which] the first two reels stop, and the third one spins a little bit longer before you get the last item on the reel. Those sorts of elements are similar to mechanisms we see in slot games.”

It’s concerning enough on its own that loot boxes in gaming share cosmetic similarities to more traditional forms of gambling, but it’s the psychological similarities that are truly worrisome.

As the discussion around loot boxes was heating up in June 2018, two professors — Dr. Aaron Drummond from Massey University in New Zealand and Dr. James D. Sauer from the University of Tasmania in Australia — partnered to write an article titled “Video Game Loot Boxes are Psychologically Akin to Gambling” for the journal Nature. In the study, they analyzed 22 popular games that utilize loot boxes using a five-part criteria to determine if risk-taking behavior is specifically defined as gambling. On this scale, nearly half of the games — many from popular franchises, such as Call of Duty, FIFA, and Madden — met the study’s criteria. Perhaps more troublingly, Drummond and Sauer’s study, as well as a later study headed by Dr. David Zendle of York St. John University, found credible links between the amount gamers spent on loot boxes and the likelihood that they were what was known as “a problem gambler.”

“Problem gamblers are people who have difficulty regulating their gambling behaviour and whose gambling behaviour causes problems in their day-to-day life,” Drummond clarifies in an email. “The Problem Gambling Severity Index is a nine-item checklist assessing the frequency of such problems. Gamblers who score eight or more on the scale are considered to be at high risk for gambling problems.”

A system that caters at any level to people who have moderate to severe gambling problems is an issue no matter what, but the target age demographic for these games further complicates matters. While most gambling is illegal to anyone younger than 18, video games don’t have that limitation.

“The reason we are concerned about them being available to minors is two-fold,” Drummond writes. “First, there is evidence to suggest that people exposed to gambling when [they are] young are more likely to develop problem-gambling symptoms later in adulthood. Second, adolescents’ brains are still developing, and accordingly they tend to have less ability to control their impulses.” In fact, according to Zendle’s study, adolescents are twice as likely to have a link between problem-gambling habits and loot box spending than their adult counterparts.

This is where stories of kids recklessly — even unwittingly — spending money that isn’t theirs comes into play. While the loot box system is not new, it’s more accessible and common than ever. And now, more countries are fighting against this model, but there’s a lack of consistency in how gambling is defined and regulated, making it difficult for any clear, international consensus to emerge.

“In many cases, there has been uncertainty about which department or departments are responsible for regulating loot boxes, … “ Drummond writes. “Some countries consider it a media classification issue, others a gambling issue, others still a consumer protection issue.”

In 2018, Belgium and the Netherlands became the first countries to have an outright ban on loot box sales in certain games. Belgium’s ban was for any loot box that can be bought with real money. The Netherlands only banned loot boxes in which the goods were “transferable” — able to be moved from person to person — and thus could be sold for real-life currency.

Other countries have taken their own approaches. China and South Korea allow the sale of loot boxes, but require the game companies to publish the success rates of the boxes openly. Australia passed a law that gamers must be 18 and up to make loot box purchases, but at press time that law had not yet gone into effect.

On the other hand, France’s independent gambling regulation authority, which is appointed by France’s president, found that loot boxes did not constitute gambling at all.

However, one factor has been uniform in almost every country: concern for protecting kids from developing dangerous habits. This didn’t come as a surprise to Abarbanel. “We’re talking about a group that has long been recognized by the gambling industry, by government members, as a group that should be protected as they develop mentally,” she says. “They’re just not necessarily prepared to understand how this might be affecting them. Now, I always like to emphasize I’m not saying that teenagers are stupid — far from it. But in general, … you just might not necessarily have the experience with these sorts of products to understand how you might be affected.”

In September 2018, 18 gambling regulators from the U.S. and Europe — including France — signed a joint statement committing to “raise parental and consumer awareness regarding the transition between gaming for leisure and entertainment and the offering of gambling possibilities.” In a letter accompanying their study, Zendle and co-authors Heather Wardle, Gerda Reith, and Henrietta Bowden-Jones called for the UK to establish a new regulatory body specifically for gaming, writing “we believe in the need for statutory mechanisms to be put in place to address the potential for adverse consequences present in industry practices.” In the U.S., the Protecting Children from Abusive Games Act proposes banning loot box sales to anyone younger than the age of 18. In a statement, U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat from Connecticut and a co-sponsor of the bill, says, “Congress must send a clear warning to app developers and tech companies: Children are not cash cows to exploit for profit.”

The issue of loot boxes is far from a settled one. As long as they make money and prove hard to regulate, game developers and executives would be loathe to remove them entirely. EA did eventually take the loot box mechanic out of Star Wars Battlefront 2, but it remains in some of its other marquee games, such as FIFA.

In a speech before the Parliament of the United Kingdom in June, Kerry Hopkins, vice president of legal and government affairs at EA, referred to loot boxes as “surprise mechanics” and compared them to the act of opening a Kinder Egg. “We do think the way we’ve implemented these kinds of mechanics is quite ethical and quite fun,” Hopkins says in her speech. “They aren’t gambling, and we disagree that there’s evidence that shows they lead to gambling.”

That being said, in countries where loot boxes have been banned, EA has complied. It seems the fight over loot boxes will continue — that is, until the next shiny, shady thing comes along and we all reach out to grab it.

This article was originally published in the Pop Insider’s Winter 2020 Issue No. 6 click here to read more!