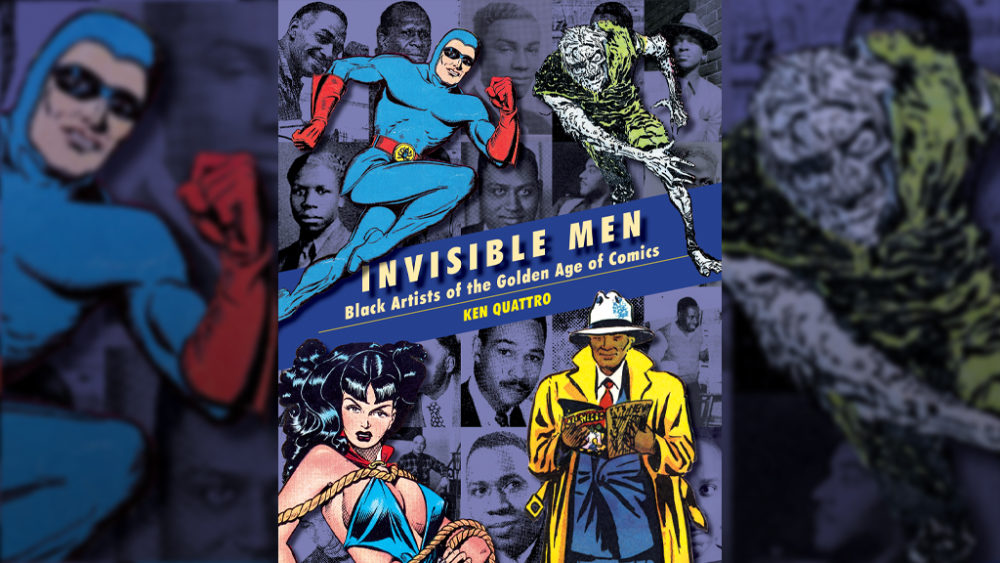

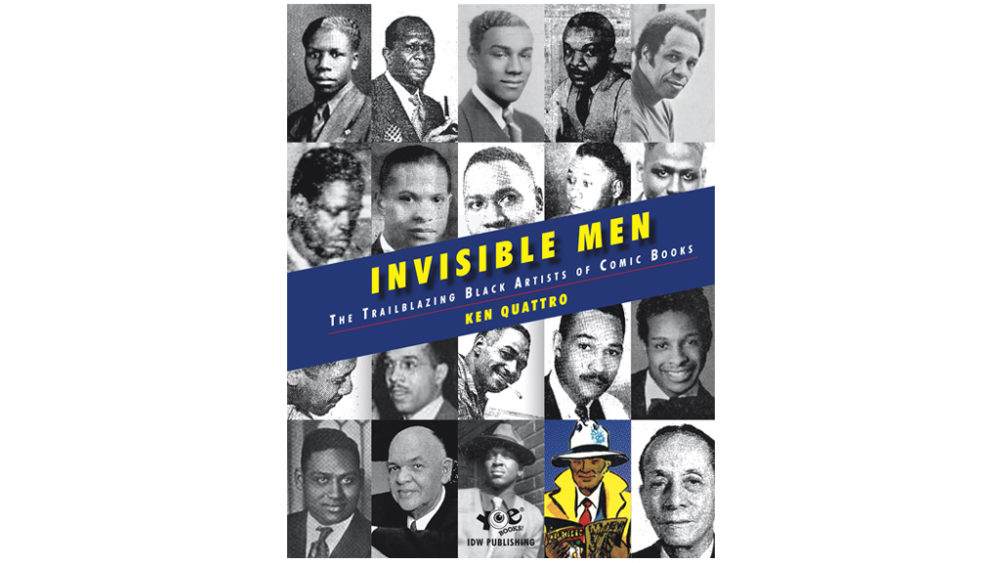

Matt Baker, Alvin Hollingsworth, Elmer C. Stoner, and Alphonse Barreaux — You may not recognize these names, but they are four artists who made significant contributions to the Golden Age of comic books, back in the ’30s and ’40s. But because they were Black men, their contributions have not been as well-documented as those of their white peers.

We chatted with Ken Quattro, whose new book Invisible Men chronicles the impact that these creators had on the comic book industry.

The Pop Insider: Can you tell us about how you got interested in this topic, and how the idea for this book came to be?

Ken Quattro: I’ve been researching and writing about comics history for decades, and about 20 years ago I was hoping to write an article about Matt Baker, one of my favorite comic book artists and probably the greatest romance comic artist of all-time. But very little was known about Baker at that time, other than the fact that he was Black.

My many inquiries finally bore fruit when someone suggested I contact Samuel Joyner, a retired Black cartoonist from Philadelphia. I wrote to Joyner and he responded with a four-page letter revealing that he had not only met Baker, but several other Black comic artists when he was a young man in the early ’50s. This information led me to start looking for further details on these men he mentioned and any other Black artists. My research eventually evolved into a mountain of data about these men and the idea that a book could be made of their stories.

PI: What was the research process like for this book, and did you encounter any major roadblocks when doing that research?

KQ: My first roadblock was realized right out of the gate when I found that there was virtually no information regarding these Black artists in traditional sources, such as contemporaneous newspapers and magazines. It dawned on me that these sources — which were all white, mainstream publications — may have overlooked the Black artists I was researching.

So, I began searching Black media of the era. It was difficult at first, since very few libraries or other institutions retained any Black newspapers or magazines. Eventually, though, after much searching, I located runs of most major Black newspapers and found that these same Black artists who were never mentioned in white media, were often noted as fine artists and cartoonists in Black media.

PI: How did you decide who to feature in Invisible Men, and is there anyone you had to leave out? Any possibility for a second volume?

KQ: I included all the Black comic book artists I found who had worked in the early years of the modern American comic book industry of the 1930s and 1940s. I didn’t leave out any other than a couple who I hadn’t yet accumulated enough data on to justify an entry in my book. Those artists and other Black artists who entered the comic book industry after 1950 will be included in a second volume of Invisible Men, which I hope will come to pass. As with any publication, sales of the book will justify a sequel. Fingers crossed!

PI: What was the most interesting or surprising thing you learned during your research?

KQ: That the Black artists I profiled were often “invisible” to even their white peers. This came about since all of them worked through various “comic shops” of that era.

Comic shops were actually studios that churned out material for publishers who didn’t have their own staff of artists and writers. The owners of these “shops” were packagers, in that they would get job assignments from a publisher to produce a comic and in turn, the “shop” owner would employ artists to produce them.

The advantage for Black artists was that they didn’t have to engage publishers in person. I came across several interviews in which a Black artist mentioned how they would never get assignments when they walked into a publisher’s office personally. Yet, by working through a comic “shop,” they could get an assignment from the shop’s owner, take it home and draw it, then turn it in and never have to confront any white publishers. Consequently, though, they rarely worked among their white peers and remained “invisible” to them.

PI: What were some of these artists’ most notable contributions to comic books?

KQ: Matt Baker was the most successful of the Black artists of the era. His work was admired by all of his peers — Black and white — and the work he did for the St. John Publications line of comics stands as some of the most beautiful artwork ever to appear in the medium.

Alvin Hollingsworth became best known for his work on horror comics in the 1950s, but he drew in a variety of genres and had a decade-long career before moving on to become a respected painter and teacher.

Elmer C. Stoner drew many comics for Dell, Vital, and other publishers, but is probably best remembered as the “Blue Beetle” artist for Fox Feature Syndicate during the mid-1940s. In the period of 1944-46, Stoner also drew every single cover for Fox’s comic book line.

And Alphonse Barreaux is historically important as the owner of the Majestic Studio, one of the first — if not the first — comic book shops, and as an artist himself beginning with “New Fun No. 1” in 1935, the first comic book published by what would eventually become DC Comics.

PI: Why is it important to tell these stories now, especially in our current political and social climate?

KQ: It would be important to tell the story of these Black artists anytime; the release of Invisible Men is coincidental to what is happening in our society right now. That said, I believe that telling these stories as I did — by detailing their personal histories and the environments they came from — is a learning experience for anyone. Black or white. By reading the life stories of these men, people get a fuller understanding of what lies behind many of today’s racial issues.

PI: Who do you hope reads this book, and what do you hope they take away from it?

KQ: I hope everyone reads it. Although I talk about Black artists, their stories are compelling to everyone. Their struggles, their triumphs, and the way they dealt with the dual lives they were forced to live — one in the Black community and the one in the white community — is eye-opening. I have had many people comment to me how all of this is new to them. And if someone learns something from what I have written in the book, then it accomplishes its purpose.

PI: What has changed — and/or has not changed — for black comic book artists since E.C. Stoner, Matt Baker, and the other artists featured in Invisible Men were in the industry?

KQ: I don’t have personal experience to refer to, as I am not Black nor do I work in the comic book industry. However, I would imagine that the systemic racism is less than it was during the era of the 1930s and ’40s. Black artists get their work published frequently and work freely in the mainstream media. That is a huge difference from in years past, but I can’t say they don’t also face some racism, personally. That is for them to comment upon.

PI: Is there anything else you would like to add?

KQ: Only that I am heartened to see such interest in my book. I hope that means that there is a growing interest in comics history in general. It is a rich, fertile field and largely unexplored. If Invisible Men sells well enough, hopefully publishers will respond by publishing more and marketing them to the general public.

Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books is available now from IDW Publishing. Ken Quattro is always writing, so be sure to check out his blogs (comicsdetective.com and invisiblemenblog.wordpress.com) to keep up-to-date on his current projects and his research process.